VeST Redux – Components, mains, simulators and test rigs

My introduction post, from way back when, focused on the idea that testing each class independently in the conventional TDD way had significant costs, and that I preferred to only test components that I expect to be used or replaced, or are out of the control of my team, or have some independent usage interface.

To achieve this, it’s important to understand what the boundary of a system is. Depending on your modeling choices, it could be an entity, it could be a subsystem, and some people even split this by RPC call.

Whatever your model, I apply the term “component” to mean any system that reacts to inputs and communicate with outputs over known contracts. This relates of course to many existing nomenclatures, but focuses on the idea that, however many classes and bits and bobs exist in a system, said system should exist logically as an independent cluster of functionality, with clear inbound and outbound boundaries. You will recognise the model from your traditional hexagonal, or plugs and adapter, architectures, as defined by Alistair Cockburn.

To reduce the friction caused by traditional class-driven TDD, I tend to test each of those clusters as black boxes, by simulating the inputs, and building test rigs and simulators for the outputs. Note that input and output here is used very liberally, as many outputs also tend to provide inputs to the system.

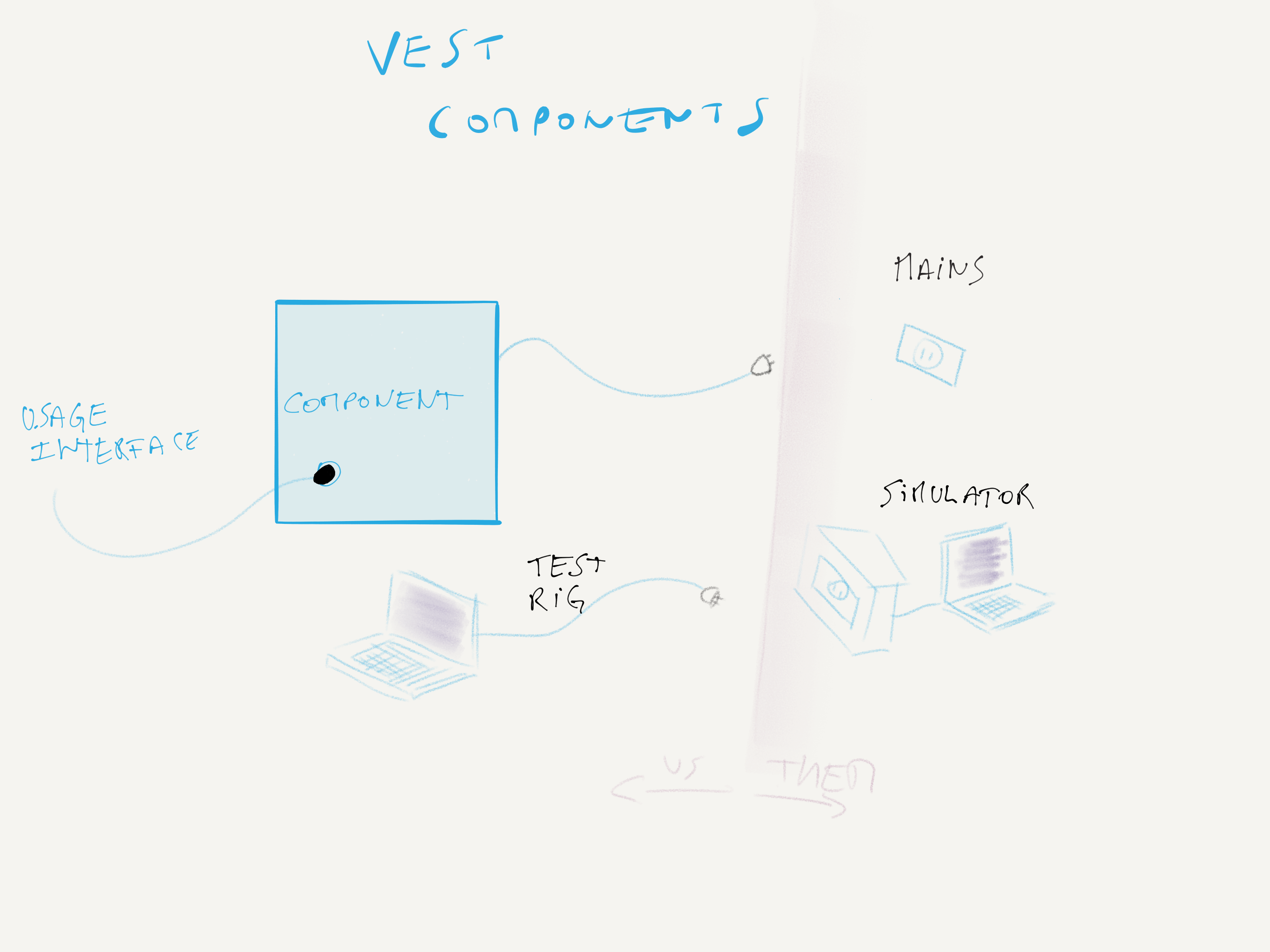

As a drawing is worth a thousand words, here’s a little diagram of what i mean.

Our component, which is usually a cluster of many classes, is a functional unit that does things we find useful. It is usually triggered through an interface, which I call “usage interface” here, and covers both UI inputs, times, and other external system triggers. I represented one inbound plug, but as you can imagine, there are usually many.

On the right side, we have what this component needs to communicate with, say, an external system, a database, a file system, a log file, whatever.

The goal of designing the system in this way is to reduce reliance on on-the-spot mocks, kill interaction testing if it has no visible benefits, and allow both ourselves and the consumers of our APIs to start testing against our systems as quickly as possible.

Other component our component-under-test uses has a contract, be it HTTP, a .net interface, or some wsdl somewhere. But relying on contract definitions only is rarely enough. To encode additional expectations, we need to encode the knowledge in code, as the single source of truth.

The mains in the diagram is an implementation of the contract on top of the system we actually want to talk to.

The simulator is another component, usually running in-memory, that encodes all the behaviours that we understand about the contract. Very often, APIs have idiosyncrasies that are not reflected in their description formats, and more often than not, that knowledge gets lost in the usual turnover our teams suffer at the hand of short-sighted resource planners. An example here would be an in-memory module that simulates the semantics of mongodb’s driver, but ensure any documet gets serialised to BSON.

The test rig is an encoding of our expectations of the contract for anyone implementing another main or another simulator. This is a set of reusable tests that others can use to make sure their implementations behave in the way that is expected by our system, aka respecting the contract, both as encoded in code, and encoding behavior as described in prose.

And of course, the goal is to ship the mains, the simulator and the test rig, and use in our own development the test rig to make sure the simulator and the mains implement the same contract.

In followup articles, I’ll give examples of how we can build that in .net.

SerialSeb

SerialSeb